A little history

Immerse yourself in the history of the Ommegang and discover its key figures.

The Ommegang

Those in power at the time in Brussels decided to show off the wealth and glory of their city by organising an Ommegang in honour of the one man who then dominated Europe and the Americas. The word “Ommegang” (which means ‘walking round’ or ‘procession’) hearkens back to the deep religious devotions of the 14th century and to the miracle of Notre-Dame of the Sablon. For this one special occasion, municipal bodies, guilds and patrician Brussels, as well as the nobility from surrounding regions and the high clergy passed in solemn procession with the pomp and circumstance that clearly announced their status and privileges, while at the same time honouring the greatness of the emperor.

In modern times the Ommegang is structured, in broad terms, as an historical re-enactment respecting historical details, but also including an amazing, spectacular fantasy of light and sound using digital technology. There is a royal court made up of descendants of those illustrious families who were in attendance the 16th century. To these courtiers is presented a veritable pageant of folkloric groups, knights, flags, stilt-walkers, marionettes, giants, and parade floats all which bring the city to life with singing and dancing, in acts of veneration, and in humour – sometimes a bit surrealistic – and which had so captured the attention of the chroniclers of the age. No other people of Europe were at that time as prosperous or as spiritedly imaginative as those of the Low Country provinces here.

With seating for thousands of spectators, today’s public can immerse itself directly in the enthusiasm, excitement, and splendour of this grand scale historical event, one which perhaps only the Palio in Sienna can rival.

Beatrice Soekens

During the Middle Ages, veneration of the Blessed Virgin far exceeded other devotions. The Ommegang was born out of this context, a history that reaches back to 1348. Brussels was at that time a city of some 40,000 inhabitants, equalling London in size. The ducal authorities had not yet constructed the last of the city walls to accommodate demographic expansion, but some 4km of walls already protected it from outside threats. The city maintained a certain level of prosperity thanks to its weaving and cloth industry, which already hinted at its development of its famous tapestry industry in the next century.

We have now come to a moment on the eve of the arrival of Wenceslas of Luxembourg for his nuptials with the duchess Jeanne. Wenceslas would make Coudenbourg one of the most frequented palaces of the time. Spared from the 100 Years War, this region was yet afflicted by the Black Plague and by roving gangs of mercenaries. A very devout woman named Beatrice Soetkens had a vision: Blessed Mary herself, the Mother of God, commanded Beatrice to travel to Antwerp where a wooden effigy of the Blessed Virgin was venerated (“Onze Lieve Vrouw op Stoksken” (“Our Lady of the wooden stick” – without doubt a former pagan goddess now repurposed). Beatrice’s mission was to bring back that statue to Brussels so that the Virgin could reward its devotion. All this may seem just a little bizarre. Of course it is true that it was never expected that Heavens, just like the Sovereign, had to explain itself or its commands.

So the excellent Beatrice, accompanied by her husband, made their way by barge first down the Senne, then the Rupel, and then the Schelde, whereupon she ran all the way to the abbey church holding that subject of her visions. The sacristan tried to stop her taking possession of the effigy, but a divine wind immobilised him on the spot. These ‘thieves for God’ could thus complete their mission without further interference. When returning, trying to retrace their passage by river (all the while consulting their maps…), the Soetkens were then beset by becalmed weather with no wind, just as an angry horde from Antwerp armed with pitchforks was approaching. Fortunately that divine gust of wind reappeared and, surrounding their skiff with St Emo’s fire, drove it at great speed up to a field which ran down from the Sablon. The Grand Serment of Crossbowmen were witness to what had happened, and were deeply moved by that supernatural luminescence and by the devotion of this uncommon thief, accompanied additionally by music “made in paradise”.

Needless to say, this catching tale evolved through the “vox populi” into a miracle with the people of Antwerp necessarily being the dupes. But these latter did however insist that the humble chapel on the Sablon become transformed into a huge gothic edifice dedicated to the veneration of the Virgin Mary, one of the largest and most beautiful churches of its type. An annual procession in commemoration was ordained: the Ommegang Procession thus was born. (The Flemish word ‘ommegang’ means literally “walking round”). And from the very start, that miraculous statuette at the centre of the story was never forgotten. For inhabitants of Brussels, it would serve as their own version of Dali’s Perpignan Station, as their own ‘centre of the universe’.

Throughout the centuries the Ommegang progressively developed into one of the most stunning events in the city. And over time as well municipal bodies, guilds and trading companies, medieval theatrical and declamatory societies, and the great confraternities and associations would replace the clergy at the head of the procession.

Charles V

Charles of Austria, born in Gent on 24 February 1500 and bearing at first the title of Duke of Luxemburg, has always been considered as “one of our own”. Nonetheless he was a member of a dynasty that ruled an empire covering Central Europe. His family, the Habsburgs, significantly increased their power when his grandfather, the future Emperor Maximilian, wed Mary of Burgundy, who had inherited the Low Countries (Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxemburg, the County of Artois) and Burgundy itself (comprising the Duchy of Burgundy as held by Louis XI, the Charolais, and Franche-Comté). Charles’ father, Philip the Handsome, added to the family’s power base by his marriage to Joanna of Castile, the daughter of King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella of Castile. (They were thus cousins.) Joanna would later inherit the two kingdoms of her parents.

Other than Aragon and Catalonia, Ferdinand II also ruled over the Balearic Islands, Sardinia, Naples and Sicily, half of Navarre, as well as over Malta and a portion of North Africa. His African conquests had even moved Pope Leo X to confer on him in 1510 the title (without dynastic rights) of ‘King of Jerusalem’. As for Isabella his wife, she had conquered the Kingdom of Grenada and, through her financing the expeditions of Christopher Columbus, had laid claim for Castile as ruler over all the Americas.

With the death of his grandfather Maximilian in 1519, Charles inherited the Hapsburg’s Austrian kingdom and then succeeded (with assistance from the banking house Fuggers of Augsburg) in being elected “Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire”, defeating thus Francis I. As of that moment he became Charles V (in Latin, Carolus quintus, hence “Charles Quint”).

After the death of Isabella in 1506, Philip the Handsome moved to take possession of the Kingdom of Castile, but died suddenly en route at Burgos (likely the victim of poisoning by his father-in-law, Ferdinand of Aragon). Charles thereby became effectively an orphan, seeing as his mother, still in Spain, had been imprisoned by her own father, Ferdinand, under pretext of being insane (accounting since then for this unfortunate’s nickname as ‘Joanna the Mad’).

The young boy Charles, on his way to becoming the most powerful man in Europe, was educated at the hands of his aunt, Margaret of Austria, and the high nobility of the Low Countries. He was very reserved in his relations with others, but held a sincere attachment to this region and its inhabitants. The beginnings of his reign were also marked the pro-French appeasement policy of his tutor, Guillaume de Croÿ. Other notable influences on him included the code of chivalry – such as was practised in the County of Hainaut, with its values of courage and loyalty – and his Catholicism, intense but also relatively open, which always led him distinguish the teachings of Christ from the otherwise dissolute ways of the clergy. His teacher here was Adrien Floriszoon, later to become Pope Adrian VI and renowned and distinguished from the other pontiffs of the time by his piety.

Charles Quint was therefore a man who straddled the Middle Ages on the one side and the Renaissance on the other, joining a concern for his own glorification with the mission that God appeared to have entrusted the House of Austria, infusing him with that celebrated gravitas of the Hapsburgs – a mix of pietism, simplicity, and seriousness. His minister Mercurino Gattinara also fashioned for him an ideology around the unification of Europe, one which the Emperor actively applied in his quest to defend the continent against Turkish expansion.

There are thus five defining characteristics to his reign:

- his rivalry with France and with Francis I and then Henry II. This led to five wars which were a significant burden on royal finances, but which did allow him to unseat French suzerainty over Flanders and Milan;

- the extraordinary expansion of Spanish control over the Americas;

- the fight against the Ottomans, whether at Tunis or Algiers, or at the gates of Vienna; and

- an opposition to the Reformation and the ongoing desire for an ecumenical council to reconcile Catholics and Protestants.

Having succeeded by election to the largely symbolic title of ‘King of the Romans’ in 1519, Charles V was crowned by the Pope thereafter in 1530 at Bologna. Following his brilliant victory in 1546 at Mühlberg against the German Protestant princes, he was able redirect his attention to the Low Countries, which he separated from the Empire itself, and then prepared the way for complete domination of the political map with the marriage of his son Philip to Mary Tudor, Queen of England. Despite the rebellion of his old ally Maurice, Elector of Saxony in 1546, the apogee of his reign occurred between 1546 and 1554. Losses and defeats thereafter, coupled with very poor health, pushed him to abdicate gradually from his various seats in 1555 and in 1556.

Nevertheless we may conclude – without stretching or exaggerating history – that on the 2nd of June, 1549, when he attended the most resplendent of Ommegang pageants in Brussels, Charles V could justly congratulate himself on a full and successful life in spite of its exhausting demands which forced him to be constantly on the road and to wage costly wars. And no doubt he could also rejoice in the deep mutual love between him and his wife, Isabella of Portugal, who was considered one of the most beautiful princesses of Europe during the Renaissance.

Even during his retirement at Yuste (in Extremadura) where he lived a calm and serene, and almost even monastic, life until his death on 21 September 1558, he was able to have the pleasure of learning of the major defeat of the French at Saint-Quentin (1557) at the hands of his son, Philip II of Spain, a defeat which ended conflicts with Valois France over Italy.

In summary, Charles V “Quint” was a very intelligent man who combined in his character those medieval values of respecting order and command, loyalty, and the submission of all sovereigns to the will of God with that of a progressive spirit, as demonstrated by his concern for European unity, and with a conviction of his solemn, single purpose to ensure the well-being of all the people which Providence had entrusted to his care. In contrast to the French kings, he put the interests of his subjects before the satisfaction of his own – but (and which may be surprising today) the condition of their souls came before their condition as citizens. For the ‘good people of Brabant’ however, he remains the symbol of an unparalleled grandeur and a genial charm, despite being just as severe to heretics as his son Philip II of Spain and despite crushing mercilessly the Gent rebellion in 1539. (Ironically for that historical event, the rebels sought to reunite with France because it did not tax as heavily.)

For our region, Charles V together with Charlemagne remain the monarchs par excellence, as being those who spread the ‘culture of Flanders’ (that is, of all the Low Countries) throughout Europe: painting, music, and tapestries all revelled in their role as being the prestigious and envied standards of the age.

Infant Philippe

Philip II (1527-1598)

The only son of Charles V and Isabella of Portugal is not remembered around here in a very friendly, happy way. Nonetheless he was still intelligent, hard-working, and physically attractive with handsome, shapely features and fine blond hair. And while being the first ‘King of Spain’ properly said, he was the one who introduced to the Iberian peninsula a love of the art originating here from the Low Countries, Burgundian etiquette, and even the name ‘Philip’.

Like his father and with the character peculiar to all the Habsburgs, he was the most powerful and the most formidable sovereign of Europe during his reign. Had he not won the naval victory of Lepanto in 1571, which allowed Spain to control navigation in the Mediterranean? Spaniards consider him a national icon yet today. He spoke only Castilian and practised an uncompromising Catholic faith his whole life through, for which the Escorial abbey-palace remains the most breath-taking expression.

Notwithstanding an occasional bankruptcy, the Spanish state wielded a might which depended on gold from the Americas, but above all on silver taken from the mines in Potosi since 1545. This flush of liquidity brought about one of the greatest inflationary periods of all time, and which circled the globe until it ended with the collapse of the Chinese Ming Dynasty in 1645, exactly a century afterwards.

Here in the Low Countries, the repression of Protestantism and the suppression of the iconoclast movement (‘Beeldenstorm’) from 1566 onwards led to the Eighty Years War, ending in 1648 with the independence of the United Provinces of the Netherlands which had become one of the major powers of Europe. Hence in spite of brutal repression by his Duke of Alba and his execution of the Counts of Egmont and Horn in 1568, Philip II can be seen as the unwitting creator of Belgium. Of course no one in Brussels would ever consider him to be “Pater Patriae”.

Even if the end of his reign was disfigured by the disastrous loss of the Invincible Armada in 1588, he had still managed to annex Portugal in 1580 and an immense colonial empire. (And contrary to popular belief, the English fleet also experienced catastrophes of like scale, such the Drake-Norreys Expedition of 1589 along the Atlantic coast of the unified Portugal and Spain with 42 ships and 13,000 lives lost, and Drake’s later 1595 expedition to South America.)

Marie of Austria

Mary of Hungary (1505-1558)

The infanta Archduchess Mary of Austria became ‘Mary of Hungary’ upon her marriage to Louis II Jagellon, King of Hungary and Bohemia. He died in 1526 at the Battle of Mohacs, when the Turks triumphed and overran almost all of Hungary. Her premature widowhood and the confidence reposed in her by her brother Charles V gave rise to one of the most remarkable reigns of the 16th century.

Like her brother, she was raised in Mechelen by their aunt Margaret of Austria. She was called to Austria by her grandfather Maximilian to complete her education, but he died before being able to do so. For reasons related to imperial politics, she was betrothed to Louis II of Hungary and Bohemia (Louis Jagiellon) while Louis’ sister (and heir), Anne of Bohemia (Anna Jagellonica), was to wed Ferdinand, the only brother of Charles V. During his reign and thereafter her regency in central Europe, Mary showed considerable interest in humanism and for the Protestant Reformation. Her two brothers, however, compelled her to refuse any dialogue between the two sides and her position continued to harden against the followers of Luther.

In trying to govern his vast empire, Charles V requested that she assume the role of governor of the Low Countries after the death of Margaret of Austria. From 1530 to 1558 she demonstrated considerable political aptitude and skills, deploying a formidable energy maintaining the financial resources of her brother while at the same time enriching the Low Countries’ economy through various measures.

A talented and enthusiastic hunter, she also had gift for military organisation, all of this being supported by a phenomenal energetic nature (which tended to hide certain depressive tendencies). She compensated for these internal shadows by demonstrating an exceptional taste in art, in music, and in literature. Her palaces in Brussels and in Binche, built by Jacques Dubrœucq, housed a scintillating court where she herself personified the grandeur of the imperial house. Moreover she frequently commissioned the greatest painters of the day (such as Titian and Antonio Moro) so that, when added to the hereditary collections of the Hapsburgs, this assemblage of art turned their chateaus into veritable galleries. We have in fact a record of the great galas held at Binche in 1547 during the visit of Charles V, where a contemporary, Brantôme, wrote, ‘Nothing was more lavish than those fêtes at Binche.’

Exhausted by the draining demands of rule, Maria (who did not like her nephew Philip) found it opportune to abdicate at the same time as Charles V. Later however, Philip II (who had remained in Belgium) sought to recall and reinstate her there. Distraught over the deaths of her sister Queen Eleanor of France and then shortly thereafter of her brother the Emperor, she collapsed en route and died on the 18th of October 1558, one month after her cherished brother and sister.

Our lady of the Sablon

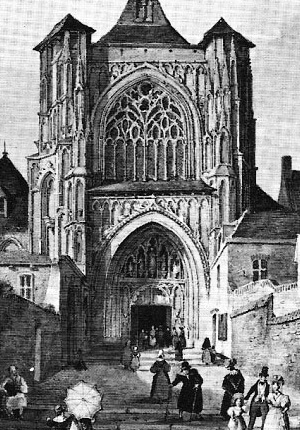

Erected in 1304 by the Order of Crossbowmen on a marshy plain, the original chapel was replaced at the start of the 15th century by the church to reflect the growing veneration by the locale populace of a statuette of the Virgin. This statuette had been removed from Antwerp by Beatrice Soetkens under questionable circumstances one night in 1348.

The notable feature of this late gothic church with pointed (ogival) arches and ribbed vaults is its choir: it has neither columns nor an ambulatory. This absence of collaterals in front of eleven 14m high lancet windows emphasises a stunning verticalising and airy effect.

Restoration work on the church began with the choir in 1864. Then in 1878 the encrustation of common buildings attached to the outer walls of the nave were removed. The work of restoration was entrusted in first instance to a local architect Auguste Schoy, and thereafter to father and son Jules-Jacques and Maurice Van Ysendyck. In the right transept, under a remarkable stone rosetta, there is a sculpture dating from the 17th century which depicts the skiff transporting the miraculous statuette.